On the evening of March 3, 1889 a sound resounded across a tiny island chain in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The sound was that of a gong and a deep rhythmic chanting in Sino-Japanese. It is a sound that has echoed across the tiny island chain ever since.

Kojima Hotel, located at #1 Beretania Street, hosted the first Jodo Shinshu (Shin Buddhist) service within the Hawaiian Kingdom. Reverend Soryu Kagahi, a Jodo Shinshu minister from Kyushu, conducted the service. This was a very momentous occasion in the history of Buddhism in Hawaii. Reverend Kagahi was concerned for the thousands of his fellow Japanese people who had migrated to Hawaii who may have been in need of some spiritual support. In February of 1889 he had embarked for Hawaii with the blessings of the Monshu, Myono Shonin.

In September of that year, Rev. Kagahi established two Buddhist communities: one in Honolulu and one in Hilo. He returned to Japan a few months later, promising to return as soon as possible. Unfortunately he was unable to fulfill his promise.

During the next several years, Jodo Shinshu followers were disorganized and extremely disheartened because there was no real leadership in the Sangha in Hawaii. They asked Honzan, located in Kyoto, for help. Honzan sent Reverend Ejun Miyamoto to assess the religious situation. Then based on Rev. Miyamoto’s report, Honzan decided to send the first official Hongwanji missionary to Hawaii. Rev. Shoi Yamada was the first to come. Following Rev. Yamada, Rev. Honi Satomi arrived in Hawaii as the first Kantoku, or Superintendent of Missions (Bishop).

Bishop Satomi wasted no time in visiting the islands of Maui, Kauai, and Hawaii to help propagate the Teachings. But soon, his health failed and as a result, he reluctantly returned to Japan, leaving behind a very troubled Sangha.

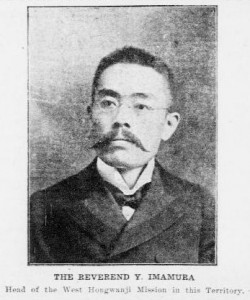

Early the following year, with his health restored, Bishop Satomi returned accompanied by the Reverend Yemyo Imamura, a 33-year-old priest with boundless energy, idealism, and a powerful vision. Rev. Imamura was asked to assume the heavy responsibility as Bishop of the Hongwanji of Hawaii. While in office, he distinguished himself as one of Hawaii’s most prominent citizens with his outstanding qualities of wisdom, compassion, non-discrimination, patience, and willingness to create positive changes.

Bishop Imamura immediately started to plan to build a temple for the Hongwanji in Honolulu. Rev. Yamada had collected enough money from the membership to purchase a temple site in Fort Lane for the sum of $2,750. Then they were able to collect $15,725 and, within a few months, a two-storied wooden temple was erected. Unfortunately, a few days before the dedication of the building, bubonic plague erupted and spread rapidly in Chinatown. To stamp out the source of the disease, a fire was set. It soon ran out of control, destroying a huge area of the city.

Bishop Imamura and the Hongwanji graciously offered the use of the temple facilities and other help to relief efforts for this terrible tragedy. Delayed by the plague and the fire, the formal dedication of the new temple finally took place on November 20, 1900.

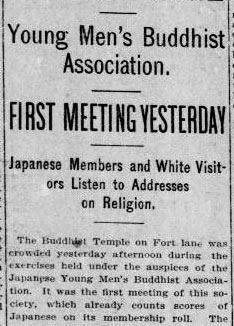

One of Bishop Imamura’s greatest concerns was the Japanese-English language barrier. In order to assist the Japanese immigrants, special classes in English were held at night as part of the activities of the Young Men’s Buddhist Association (YMBA). The YMBA also began publishing the magazine, “Dobo” (Brotherhood), and lectures on the essentials of Buddhism were regularly held. Social and athletic activities increased, and the membership soon reached 250. In 1923 a new YMBA building was built on Fort Street for $63,000. The inter-island YMBA Federation, formed in 1927, was in 1935 renamed Hawaii Federation of Young Buddhist Associations. The Honolulu YMBA retained the name until 1947, when it was renamed Young Buddhist Association of Honolulu.

The Women’s Buddhist Association (WBA), Bukkyo Fujinkai, in Honolulu was inaugurated in May 1898, under the leadership of Mrs. Kiyoko Imamura, wife of the Bishop, and who was a devout Jodo Shinshu Buddhist. The 1,080 members pledged themselves to the four “‘L’s” namely, Life, Light, Labor, and Love.

In the early days, an event occurred that had far-reaching consequences. On May 19, 1901, Queen Lili‘uokalani, accompanied by Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Mikahala Robinson Foster, a wealthy part-Hawaiian Buddhist and a dear friend of the Imamuras, attended the Hongwanji Gotan-E services, commemorating Shinran Shonin’s birth.

The presence of the recently deposed Queen of Hawaii at a Buddhist service caused quite a stir in the community and was reported widely in the newspapers throughout the world. Bishop Imamura later reported that for the timid young Buddhists the visit had a very positive impact, raising self-esteem and confidence in them.

In 1906, the Reverend Zuigi Ashikaga, who headed the Department of Propagation at the Honzan, arrived in Honolulu bearing the announcement that henceforth the temple in Honolulu would have the status of Betsuin, or “detached main temple,” and would serve as the headquarters of all the temples in the islands. In the following year, the Territory of Hawaii recognized the incorporation of the Hongwanji under the name Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii.

It was about this time that Mrs. Mary Foster donated a large portion of land—on which the Fort Gakuen Japanese Language School and Hongwanji Mission School now stand—to the newly incorporated Mission. In addition, she donated a sizeable amount of money to the Hongwanji. The present Betsuin structure took two years to build from 1916 to 1918, at a cost of $100,000 collected from members and friends throughout the islands.

In 1975, the Giseikai (Legislative Assembly) approved a reorganization plan that separated the offices of the Bishop and the Hawaii Betsuin Rimban (Chief Minister), with the Bishop to appoint the Rimban. The Mission and the Betsuin are distinct organizations, each with its own budget, board of directors, and office suites. The organizations share the temple campus with Pacific Buddhist Academy.

Bringing the Buddha’s message of non-violence, self-reflection, and peaceful cooperation, the missionaries traveled to and from plantation camps on foot or horseback. The ministers helped the immigrant workers with their letter writing, conducted funeral and memorial services, counseled the downhearted, discussed the problems of the community, arranged marriages, arbitrated family disputes, took in orphans, and settled labor and management problems. They were also asked to keep good vital records. Much of the work was done at a great personal and material sacrifice.

In the early years, the Buddhist clergy were sorely criticized by the Christian community because of their tolerant attitude towards drinking, gambling, prostitution, and other social vices, but soon their sincere efforts in bringing spiritual values to the workers began to have a dramatic effect on the moral life of the community. For the Japanese people, the ministers served as a stabilizing force, bringing a sense of honor, duty, responsibility, and justice through knowledge of the wisdom and compassion of the Buddha.

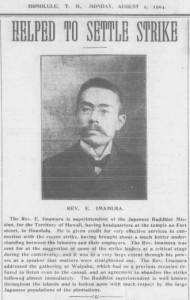

Leading the way was Bishop Yemyo Imamura who had a wide and deep understanding of the problems faced by the immigrants. The people responded to him because his earnest and genuine wish for their happiness was always evident. Bishop Imamura had a strong role in settling the Waipahu strike in 1904. He wrote, “Revealed within our nature is the ugliest and saddest spectacle. If we honestly recognize this truth, it is nothing but a monstrous conglomeration of greed, passion, and folly.” The Bishop identified himself, too, as being one of the ugly human beings, referred to by the Buddha, and he encourage the workers to follow the Buddha’s teaching of self-realization, compassion, and wisdom, which would lead to a thankful heart, and universal brotherhood would prevail. He advised the workers to go back to work and the strike was resolved.

The immigrants began focusing their energies on building their communities and improving the quality of their lives by constructing temples, language schools, and practicing their religion. It was the Buddhist influence and support that made life on the plantations tolerable by strengthening family relations and elevating moral values.

Caucasian teachers were asked to help the workers assimilate in American society. In October of 1921, Ernest and Dorothy Hunt, two people in sympathy with Buddhist perspectives were asked to teach the young people of Japanese ancestry in Hilo. About three months later, Rev. M. T. Kirby of California came to Honolulu to serve at the Fort Street temple, and through his weekly classes on Buddhism enabled non-Japanese Buddhists and locally born people of Japanese ancestry to gain some insight into Buddhism. Bishop Imamura recalled the Hunts to Honolulu, who had labored and studied on the Big Island, to receive ordination. The Hawaii branch of the International Buddhist Institute was established, and, under the guidance of Reverend Hunt, many young people were attracted to the non-sectarian activities of the organization.

Early in the morning of December 22, 1932, a male member of the temple, hysterical with grief, ran into the study where Rev. Hunt had been waiting for the Bishop, screaming, “Bishop Imamura ma-ke! Bishop Imamura ma-ke,” Bishop Imamura had passed away.

The 65-year-old Hongwanji leader had died of a heart attack. Bereaved Buddhists mourned his death for months in public and private services. Christians, dignitaries, and Buddhists paid tribute to the memory of one of the most remarkable religious leaders in Hawaiian history. A quote from the late Bishop Imamura states, “The entire Karma of events through the decade, from the beginning to this day, is nothing but the manifestation of the Compassion of the Buddha.”

After a brief interim tenure of Bishop Zuigi Ashikaga, who arrived in October of 1933, Honzan appointed the Reverend Gikyo Kuchiba to be the next Bishop. Bishop Kuchiba’s six-year term ended with the fateful attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941.

World War II totally disrupted Buddhist activities in Hawaii. On December 7, 1941, the Buddhist community was busily preparing for Bodhi Day services at various temples. The next day the temples were closed, and the Buddhist ministers were interned. Labeled “potentially dangerous enemy aliens,” most Buddhist clergy, language school teachers, community leaders, businessmen doctors, anyone who had been identified as possible enemies of the United States, were rounded up to be taken away to detention camps, passing through the assembly center at Sand Island on O‘ahu.

In Hawaii, the closing of the temples and the internment of the ministers put the mental and spiritual health of the Issei in a state of shock. The temple was an important part of their existence, but the cruelest shock of all came when loved ones who had died had to be buried without Buddhist services. Even memorial services could not be held for the lack of ministers.

A few months after the cease-fire in the Pacific, the ministers began to return from the concentration camps and immediately set about restoring the neglected temple buildings as well as rebuilding the congregations.

Immediately after the war, the ministers and lay leaders came together to choose the first elected bishop, and after a serious deliberation the Rev. Ryuten Kashiwa was selected by consensus. Since that first election in 1946, a democratic process in which minister and lay representatives assembled to choose their spiritual head every three years has selected all sequent bishops. As of 1999, the Bishop’s term has been changed to four years.

In 1952 Monshu Kosho Ohtani and Lady Yoshiko Ohtani Visited Hawaii for the first time and spent 42 grueling days touring all the islands and participating in memorial services, confirmation rites, and receptions. They returned to Hawaii again in 1954 to officiate at the 65th anniversary of the founding of the Hongwanji in Hawaii.

In the same year, Buddhist Boy Scout organizations received the authorization from Dr. Arthur Shuck of the National Council of the Boy Scouts of America to award Boy Scouts a Buddhist religious award called the Sangha Award. It was through the efforts of Mineo Yamagata, who was Executive Secretary of both the Honolulu YBA and the Hawaii Federation of YBAs, and Stanley Okamoto, who was at the time a very active member of the United YBA of Maui, that the Buddhist Scouts were brought up to par with scouts of other religious affiliation. All Buddhist groups use the Sangha Award both in Hawaii and on the mainland.

In 1949, one of the most momentous decisions made by the Hongwanji after the war was the adoption of a proposal to establish the Hongwanji Mission School, the first Buddhist, English grade school. In 1992, the Hongwanji Mission School became available for students up until the 8th grade. Prior to that, the school was an elementary school with students from preschool to the sixth grade. In September of 1993, the middle school building was completed, and the class of 1994 was the first class to occupy it.

In the fall of 2003, with the encouragement of Bishop Chikai Yosemori, the Pacific Buddhist Academy opened its doors to the first class of fourteen students. PBA is a college preparatory high school, and the first Shin Buddhist high school in the western world. The school’s mission is “to prepare students for college through academic excellence; to enrich their lives with Buddhist values; and to develop their courage to nurture peace.”

Pieper Toyama was the founding Head of School and served for ten years to 2013. The current Head of School is Josh Hernandez Morse. In 2016, the school will graduate its tenth class of seniors and begin construction of a new classroom building.

The tenth Bishop of Hawaii, Bishop Kanmo Imamura, was called from Berkeley, California where he had been in charge of the Buddhist Study Center there. It was his inspiration that established the Buddhist Study Center also in Honolulu. With the help of Dr. Alfred Bloom, two properties adjacent to the University of Hawaii were purchased.

In August of 1972, the BSC was opened with a three-pronged thrust: a student center where University of Hawaii at Manoa students could meet, a ministerial training center where aspiring young men and women could receive instruction not available at the university, and a study center where Buddhist lectures and study classes could be held. Initially the property was three houses next to each other, but in 1995, the renovations for a large, single facility were completed.

Every year since the opening, a summer session has been held attracting a growing number of participants and Jodo Shinshu as well as non-Jodo Shinshu professors and scholars. There have been many prominent minds who have lectured at the Summer Sessions, such as Dr. Alfred Bloom of University of Hawaii, Dr. Taitetsu Unno, and Dr. Carl Becker.

The Ministerial Training Seminar continues to be offered twice a year, in spring and in autumn, and adult education series are given throughout the year—many offered through the Dharma Light Program. The Fellowship Club has been continuing for many years, and people from the community have graciously come forth to offer their time to share interesting aspects of their lives with a group of people of various interests.

The Buddhist Study Center has become a significant avenue for the expansion of awareness of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism. The many seminars, retreats, summer sessions, and publications provide rich accessibility to the relevancy of Jodo Shinshu teachings.

A project that was well received in the Buddhist community in Hawaii was the effort to establish the Buddha’s birthday as a state holiday. The Federation of YBAs, with the leadership of Charles Sakaguchi, its President, collected 40,000 signatures to petition the legislature. Buddhist leaders, including Rev. Yoshiaki Fujitani, appeared at the legislature to testify. On April 8, 1960, a bill sponsored by Representative Jack Suwa and Senator Kazuhisa Abe became a law, establishing Buddha Day, not as a holiday, but a “holy day,” which simply meant it was a special day, although it was not a legal day of rest. This recognition gave Buddhists in Hawaii a boost in their self-image.

Another project that received a lot of support from not only the Buddhist community, but also the Hawaii community, was the adoption of Peace Day. The idea came from the United of Oahu Jr. YBA’s member Tracyn Nagata and advisor Claire Tamamoto. Peace Day would be a day when all persons, regardless of religion, can officially celebrate and embrace peace throughout the world.

Another project that received a lot of support from not only the Buddhist community, but also the Hawaii community, was the adoption of Peace Day. The idea came from the United of Oahu Jr. YBA’s member Tracyn Nagata and advisor Claire Tamamoto. Peace Day would be a day when all persons, regardless of religion, can officially celebrate and embrace peace throughout the world.

With the sponsorship of Representative Jon Riki Karamatsu, Federation of Jr. YBA president Casey Fukuda, and Federation of Jr. YBA Secretary Robyn Taniguchi worked to have the bill become law. The bill specified September 21 (coinciding with the United Nations’ World Peace Day) as Peace Day in Hawaii. On April 18, 2007, Governor Linda Lingle signed the bill, making Hawaii the first state in the United States of America to recognize September 21 as Peace Day. The Peace Day Parade held in Honokaa on the Big Island is officially recognized as an official United Nations activity.

Drawing inspiration from the Living National Treasures (Ningen Kokuho) of Japan, insurance executive Paul Yamanaka knew there were many people in Hawaii who deserved similar recognition for their contributions to the preservation and perpetuation of the Islands’ distinctive cultural and artistic heritage. This program recognized those people who quietly practiced their craft to enhance the lives of others.

Bringing this idea to Bishop Yoshiaki Fujitani, the 11th Bishop, the Living Treasures of Hawaii program got underway. Bishop Fujitani wasted no time to gather a committee of experts in Hawaiiana and practicing artists actively involved in the Hawaiian community. In the committee was John Dominis Holt, publisher; Pi‘ianai‘a, University of Hawaii professor; Zenetta Ho‘ulu Cambra, chanter; Rubellite Johnson, translator of Kumulipo; Homer Hayes, historian; and Cecilia Lindo, Hongwanji Mission School teacher. Mr. Yamanaka served as chair and Bishop Fujitani was an ex officio member.

The first recipient of the award was Charles W. Kenn, noted scholar, historian, author and practicing kahuna in an informal ceremony held at the Hawaii Betsuin in 1976. Since then the Living Treasures Program has recognized many writers, educators, artists, musicians, professionals, and volunteers.

Project Dana is an interfaith volunteer caregivers program started in 1989 and sponsored by Moiliili Hongwanji Mission. The Project provides support services for frail homebound elderly, disabled persons, and family caregivers, thereby contributing towards their well-being in their desire to enjoy continued independence with dignity. Built around the universal principle of “Dana,” which means “selfless giving,” Project Dana’s mission is to provide selfless giving of time while providing compassion and care without the desire for recognition or expression of appreciation.

Video profile of Project Dana founder, Shimeji Kanazawa.Volunteers are the “heart” of The Project, as they put dana into action. They make friendly home visits; provide transportation for grocery shopping assistance, medical appointments and church services; allow respite for the caregiver; make telephone visits and conduct home safety assessments. Other support services are nursing and care home visits, minor home repairs, yard maintenance, light housekeeping, senior activity programs and spiritual and emotional comfort. A highly successful caregiver’s support group meets several times a month.

Project Dana is comprised of a coalition of churches/temples on Oahu, Hawaii, Maui, and Kauai. Volunteers receive initial and continual training, education, and guidance from The Project’s staff and professional resource people. Volunteers are sensitive to diverse cultures and traditions and provide bilingual services. This highly successful outreach program has gained national and international recognition and is a model which other religious organizations are emulating.

In 1998, the Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii was fortunate enough to host a statue of Rennyo Shonin sent from Yamashina Betsuin. Although Rennyo Shonin passed away in 1499, Hawaii observed the 500th memorial service with the statue. Hawaii was the only district that was fortunate enough to host the statue. It was first sent to the Hawaii Federation of BWA convention on Kauai, then to the other islands to host a memorial service on each island.

A program for youth that has been successful is the Young Enthusiastic Shinshu Seekers camp. Rev. Sandra Hiramatsu started the camp. Inspired by her concern in bringing Jodo Shinshu to the youth, she sought to refocus the young people’s attention on basic ideas taught by Shinran Shonin. The first YESS camp was held at Camp Kokokahi in 1984.

Based on the idea and success of the YESS camp, a Junior YESS Camp was started in 2002 to build a bridge between Dharma School, Jr. YBA and YESS Camp. Ann Ishizu, former Children and Youth Specialist, created the first camp, held at Camp Timberline for students in grades 5 to 8. Unlike the YESS Camp, the Jr. YESS Camp is held every other year.

Based on the idea and success of the YESS camp, a Junior YESS Camp was started in 2002 to build a bridge between Dharma School, Jr. YBA and YESS Camp. Ann Ishizu, former Children and Youth Specialist, created the first camp, held at Camp Timberline for students in grades 5 to 8. Unlike the YESS Camp, the Jr. YESS Camp is held every other year.

As we reflect upon and express our gratitude for the hard work and sacrifice of those who came before, let us look to the future so that the Dharma will continue to flourish for generations to come.

Most text on this page comes from a history prepared for the the 120th anniversary of the Honpa Hongwanji in Hawaii in 2009. Use the headings to display specific parts of the history.

Most text on this page comes from a history prepared for the the 120th anniversary of the Honpa Hongwanji in Hawaii in 2009. Use the headings to display specific parts of the history.